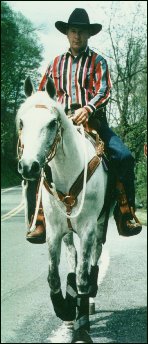

Equerry Exclusive Interview with

John Lyons

Judi Gerhardt prepared questions and Brian

Scrivens interviewed John Lyons during a seminar conducted at Hilltop Farm,

Inc. in September,1997. Our

questions, and his answers, are presented below.

| Background: In the past sixteen years,

John, one of America's most popular trainers, has personally worked with thousands of

horses. In the same time, he has given nearly 300 clinics and 250 symposiums with the

average attendance of 300 horse owners. At special events, such as Equine Affaire,

Equitana, Hoosier Horse Expo, Minnesota Horse Expo, Midwest Horse Fair and many others

where he has been a featured speaker and demonstrator, his collective audience attendance

is well over 100,000 horse owners. John has been a featured speaker on local and national

television and radio programs. CBS This Morning, a national morning show,

featured John as America's "Horse Whisperer". John's three books, fifteen

videos, audio series, quarterly newsletter, and monthly magazine have become some of the

most sought after educational materials on training. The monthly magazine "John

Lyons' Perfect Horse", in its first year of publication, reached over 30,000

readers. John and his wife, Susie, have four children, two grandchildren (with one more

due in December 97) and live in Parachute, Colorado. |

|

Click on the above logo

for John Lyons' Web site.

[Click on the

Equerry.com logo at the top of this page for Equerry Home] |

|

Equerry: John, you have written numerous books and articles and held

clinics throughout the U.S. for years. What is your most frequently asked question

with regard to training?

John Lyons: The most frequently

asked question is, "How to solve a problem".

The problem could be biting, it could be rearing, it could be the horse tripping on the

trail, it could be any injury-type problem. Basically, people are trying to make their

horses safe to be around, for people to be around. What I try to teach is to focus on what

you want rather than what you do not want.

I practice a replacement theory. It started as a "walk & chew gum theory".

The walk and chew gum theory is this: we can walk and chew gum, but if we add one more

thing to walk and chew gum, such as talk to a friend and walk and chew gum; talk to a

friend and pat your head and walk and chew gum, et cetera. At some point in time,

if you add enough so you cannot chew gum, which is the thing I do not want you to do, then

what I’m doing is not focusing on telling you don’t chew gum. What I’m

focusing on is telling you what I want you to do by continuing to add one more

thing. The walk and chew gum theory developed, for me, into the Replacement Concept.

The Replacement Concept is to NOT focus on the problem, focus on the desires of the

person, what they want. Replace the bad behaviors with what I want. I crowd out bad

behaviors with good behaviors. I try to teach people to not correct a horse. If we can

avoid ever scolding our horse we are far better off. Whenever we scold a horse we get

unwanted behaviors – the ears pin back, the tail wrings, et cetera. All

those things are unwanted behaviors we do not want to train. If we scold him, we might get

him to stop doing what it is we don’t want him to do. But we may also create some

side effects we do not want.

My theory is: "How can I find a better way to get rid of the unwanted behavior

without causing the extra work of having to come back and fix side effects?" The

Replacement Concept is simple. When the horse is doing something I do not want, I focus on

what I want. Eliminate scolding and make all corrections small enough and smooth enough

that if someone is watching they would not know your horse made a mistake. To me this is

the ideal way to correct a horse. The rider’s movements and corrections, no matter

what the horse is doing underneath the rider, are fluid enough it does not look like the

rider changed at all. Even though the horse is screaming, or he goes twenty feet to the

side, the rider stays focused on what they are doing, soon the horse comes in line with

the rider and begins doing what the rider wants. The rider does not react to the horse and

change their program.

To understand the concept takes practice, it takes a real desire for the person not to be

normal. "Normal" for us is when a horse is doing something wrong, to get after

him or scold him. For example, when the horse bumps into you, the "normal"

reaction is [a slap] ‘hey get off of me’. Why not ask the horse – "how

about breaking at the poll, or soften your neck and your shoulders and move away like

I’d like you to." It is so much more "normal" for us to just slap him

or grab him real quick and scold him rather than think ‘the reason he is bumping into

me is because I’m not asking him to do something I want him to do’.

It takes practice, but it is achievable by anyone. It doesn’t make any difference

what style of horse you’re riding or the type of riding you do – whether

it’s trail riding or upper level dressage, everyone can put that program into

practice and benefit themselves and their horse.

Equerry: In your mind, how do

the principles of training that you demonstrate and teach apply to disciplines such as

dressage and jumping?

John Lyons: All disciplines are

the same in terms of what we are looking for.

We might change the head position a bit, one style of riding might have a bit more bend to

it in the body or flexibility – but basically, if you break down all the styles of

riding we are all looking for a more responsive horse. More responsive means the horse

does more of what the rider asks with less work from the rider. We want a more

responsive horse so we can direct and move him around the dance floor or wherever it is we

want to move him. That’s all a trail ride is, or an arena – a dance floor and we

are dancing with this partner we happen to be riding.

If we are looking for better ‘collected’ horses, well, a definition of

collection is to bring together two or more things to a central point. You cannot collect

a horse from either one end or the other, it simply will not work – you have

to bring them both together. In order to do that the horse must respond to two individual

aids. For example, the hind quarters: In order [for you] to bring up energy from the hind

quarters, the horse has to respond to a cue, whether it’s a two-legged cue to go or

your seat, so that when we give the aid we get a lot of energy from that horse. The other

aid we need him responsive to is the bridle, so we can direct the energy we get. Whether

you are riding a reining horse or a dressage horse, it requires the same two responsive

ends.

If you are jumping a horse but cannot guide him, cannot move him around the dance floor to

get him in the center of the jump, or where you want him to turn, then the jumping is

over. If you are approaching a jump and the horse is running away and you pick up the rein

but he does not respond, all he does is fight, he becomes non-responsive to the bridle and

you are in trouble. It is the same thing for gaited horses. The more you look at the many

different styles of riding you will see we are all doing the same thing, we’re all

trying to get more response to those two aids.

The common threads are: getting horses in and out of the trailer; getting them not to drag

us off; getting them not to bite us. Everyone is going to deal with these types of things

– every breed. Stallion owners worried about getting mares bred without getting

killed, etc. We put different saddles on them, put on different clothes but it is really

all the same. The common thread of top riders of any discipline is they have the desire to

learn, they have the willingness and open mind. They have a good work ethic. They work

hard and I would say, to a great extent, they are all very caring about their horses, in

general, they like horses.

I try to teach people if they want a good reining horse to go ride dressage horses if they

want to improve their reining. If you’re a dressage rider go fool around with some

other breeds and ride some reining horses – it will help your dressage. Although they

do not match exactly, there are some principles you can apply from one style of riding to

another style which will actually improve that style – learning is learning. (I would

say 95% of horse training is learning what not to do, that is a major part of our

learning – to eliminate sending signals that develop performances we do not want.)

A lot of riders get stalled out, get stale if they stay strictly with what they are doing.

Even though they are trying not to become bored with it, they do become a bit bored. As

soon as they become bored they become stagnant in that area. Sometimes just getting out

and doing something different with their horse, or riding a different style of horse, will

freshen up one’s attitude and desires for the particular style of riding one has

chosen.

Equerry: What encourages you

most about riders and trainers you encounter?

John Lyons: What encourages and

inspires me most are people who come who are 60, 70 and 80 years old and still want to

learn. They inspire me because they are still so full of life.

We had a 67-year-old lady riding this young, thoroughbred horse, a good quality horse but

just needed a little more work. This lady was so sharp, her hands and motor skills were

outstanding, and I could explain what I wanted her to do and she could do it. She was very

horse knowledgeable, she’d been riding all of her life. I just get tremendously

energized with a person like that.

We had a 92-year-old fellow this year who sat through the whole symposium and clinic

– 6 days in a row. He’s a cattle rancher and still wants to learn. One of the

things he wanted to know was how to get a horse to stop rearing up – just an amazing

thing.

I am also inspired when I get to meet and visit with the top riders in the country, the

cream of the crop of whatever discipline they are in. I see these folks always have one

characteristic in common – they always want to learn. It is like there is a mad dog

on their heals trying to catch them all the time. It has nothing to do with competition,

it has to do with their desire to learn more. Even though they have learned so much they

still recognize there is much more to learn. Their desire is like a drive, it’s a

desire to learn more and that also inspires me to want to learn more, to go through the

effort.

[I am also inspired by] the average horse owner whose horse is just beating the snot out

of them, hurting them and they have ended up in the hospital, yet they love these horses

so much they want to learn how to handle those problems. When I receive letters and

comments that I saved their life or I saved their horse’s life, that they were at

wits end and were told to put the horse down. They felt that it was the last straw and the

information I gave them helped change their life or their horse’s life – those

things are important and encourage me.

Of all those things the one thing that’s more important is the people who come and

they understand that the training doesn’t actually come from me, it comes from God.

It comes from his knowledge of the horse. They recognize the most important thing in their

life is a relationship with God first. Our relationship with our family has to be right,

and then with other people. When we get all those things correct what happens is the horse

ends up correct, it allows our heart to do the right thing at the right time.

Equerry: From your

observations, what training concept do riders most frequently omit when training a horse?

John Lyons: FUN!

Fun is probably omitted the most, especially in people who are showing and feel the

pressure of the show ring.

My parents told me, and I am sure many parents have told their kids this, that when you

choose to marry, whatever problems you have before you get married – multiply that by

10 or 20. That’s how many problems you are going to have after you get married.

That’s how many differences, arguments, etc. you will experience. That is certainly

true and for the horse it’s the same way.

If I am aggravated, if I am frustrated and I am not having a very good time, what I need

to do is multiply that by 10 and that is how much fun the horse is not

having. The horse does not want to be there anyway. This is our game not his – he is

fine left alone out in the pasture – "just leave me alone in my world and I will

be just fine". We want to bring him into our world, we want the lead changes,

we want the sliding stop, we want him to go over jumps, and we want him to do all these

different things. Those are desires on our part, not his. We have to recognize he does not

want to be there.

If we are poking and prodding him and aggravating him and we are frustrated because some

one is beating us at the show or because the horse is not doing what we want, we start

drilling him and then we are not having any fun. That aggravation is going to come out in

the horse. It is going to come out somewhere in the horse’s performance, his ears,

his tail, he is going to stiffen up his body and become more aggravated through his work.

His performance is going to become rougher and he is not going to enjoy his work. This

lack of enjoyment is going to come out somewhere in his performance. Something we do not

want as a behavior.

One of the most important ingredients to keep in our training is fun. To make sure we are

having a good time so we transfer that feeling of having a good time to the horse. We get

wrapped up into what happens and do not mean to leave the fun out of it. Someone gets a

horse for the concept of the love and enjoyment of the horse, then they find out "oh,

look how much more he can do". We begin to get wrapped up in the performance and then

wrapped up in the show. Then we bring a measure, we have to do better.

It is like owning a pet - I’ve owned dogs most of my life but it was completely

different owning a house pet that is your friend and runs around with you. Owning a dog on

a ranch is different, you expect the dog to do a job, he is earning a living. On a ranch

you move cows, if the cows are in the brush you need that dog to go in and get them. It is

a completely different relationship now.

That is what happens to us when we show, when we compete – now the horse has a job.

If he does not do his job, like anybody who doesn’t do their job, the relationship

changes. It is no longer "drop the reins and let’s just go play on a trail ride,

let’s have a good time and let me hug your neck – if you don’t stand

exactly perfect and you are not collected all the time, who cares." Instead, we begin

to ask more and more. Demanding more and more and expecting more. What happens is that

relationship begins to change, which is no different between people.

You and I can be real good friends we can have a great conversation. As soon as I start

expecting things from you, all of a sudden there is a pressure – well, you did not do

what you were suppose to. That happens between kids and parents, husbands and wives,

bosses and workers – the fun is no longer there!

Equerry: With

regard to the "Replacement Concept" you detailed in the first question, and the

points you have just made (in the previous question) about omitting fun, if a

horse is not doing what you want and you get him to do 5 other things, is your advice to

simply look for what’s fun to do next in order to avoid frustration?

John Lyons: If you are feeling too aggravated, if you find yourself not enjoying

your riding lesson that day, sit and write down why you got a horse to begin with. What

was the purpose, what inspired you to get a horse, another thing is to write down your

values. Is it the most important thing to win at all costs?

Generally, when people are not feeling good about what they are doing on top of their

horse it is because they know in their heart they are doing things that they should not be

doing. The frustration really has nothing to do with the horse. The frustration comes from

inside the person. The reason the frustration is there is because the person is not

satisfied with what they can do, what they can accomplish.

That’s a good characteristic, not necessarily a bad one. It is a characteristic that

pushes people to want to learn more, to do better, and to expect more of themselves. While

they expect more of their horses they expect more of themselves. They have to recognize

the frustration comes from trying to do something they do not know how to do. They are

trying to teach this horse something they do not know how to teach them to do. It has

nothing to do with the horse as an entity. It has to do with the type of person they are

– they are not satisfied with what they can do, they want to do better, want to learn

more.

The 1st point is to recognize the horse has nothing to do with the frustration

and the aggravation.

Then 2nd is to recognize you are not a quitter. If you do not learn it today,

you are not going to give up, you will learn it tomorrow and if you do not learn it

tomorrow, you will learn it next week or next year. You are not into it for the short

term, you are into it for the lifetime hobby so you have a lifetime to learn it.

The 3rd thing to recognize about this is really important: as soon as you learn

it, the words are going to come out of your mouth, "Well, I can do that, now I want

to do this". The whole cycle starts all over again. It’s a constant, a lifetime

of frustration. You have to get a handle on it, recognize it for what it is. Recognize you

are going to deal with it. If it gets too bad, step off the horse, hug the horse,

put the horse up or spend a couple days just going in his stall and rubbing on him. Develop

the relationship again.

Recognize that the most important thing is not winning the trophy today, the most

important thing is winning the trophy sometime. Do it in a way you feel good about [it

all] along the way. Winning the trophy is just momentary. Anyone who has won the

Olympics can tell you, it’s a momentary thing. The next day they are already thinking

about the next Olympics because they have to do it all over again.

If we chase the goal, if we chase the buckles or the trophy – the trophy in itself is

a major disappointment. It is the trip getting there, it is the knowledge, the growth and

the effort that we put into getting there that makes its all worthwhile, it is not

the end itself.

Equerry: If you could implant a single

understanding in the minds of all riders, handlers, trainers and instructors – what

would that be?

John Lyons: Consistency.

Consistency comes from the ability to concentrate. If we could learn to focus and develop

our own concentration then what would happen is: we would become consistent. When we

become consistent the horse picks up on the language we are developing. Concentration is

the most important single factor in being successful in any field.

Equerry: What are the main differences in training

a young horse and a "problem" horse?

John Lyons: There are no differences, they are all the same.

I do not change the routine. I just take and do my thing and then the horse

eventually comes in line. Again, I don’t focus on any problem. I

just focus on what I want the horse to do and then I start through the training process.

Wherever the horse is in training, I start and build from there.

I don’t change me to fit the horse – I have the horse change to fit me.

Equerry: What

is your greatest reward from the teaching you do?

John Lyons: When people accept Christ in their life.

They come to that through being exposed and having the opportunity to understand:

Christ really does love them;

Why God created Adam and Eve in the first place;

Why He sent His son here to die for our sins and us.

Developing that relationship is by far the most important

thing we ever do for people or that God ever does through me.

Equerry: If you could enlighten

breeders about producing certain traits or qualities, whether anatomical or character,

what would you tell breeders?

John Lyons: Breed for performance, not for looks.

If we breed for looks we’re breeding for a concept of what we think is pretty and

pretty is not necessarily functional. We need to breed for performance always and then

beauty will come along with it. Pretty is as pretty does. Do not breed because we think

its pretty because it may end up unsound.

Take the dog world – I don’t understand why they take and breed a dog whose legs

are so crooked you know when that puppy hits the ground he is going to go through a lot of

major pain. It would be like breeding kinds of mental defects and deficiencies and

physical deficiencies. Why would we do that with our horses?

We need to breed for functionality so they stay sound and they can move, they can do the

things we want them to do - not because they have a pretty head.

Equerry: During your symposiums, you

mention setting goals as a part of training a horse. What do you believe are the key

elements to achieving your goals in training, in business or in life in general?

John Lyons: The first

thing in setting goals is learning how to set elaborate goals. Make sure it is a well

defined goal. The goal tells us what kind of methods we can use along the way to get

there. It tells us in many cases what we have to do, and the many steps we have to take to

get there. Learning how to establish a correct goal is important. If we do not have a goal

we do not know where we are going. The odds of us getting to where we want to be are just

absolutely remote – astronomical.

The important part of developing a lesson plan is learning how to identify a beginning

point. A beginning point has to do with several things, like the 1st page of a

book, it might even be the introduction in the book, explaining what the book is about but

not going into detail about it. The beginning point is where we start off on the right

foot with the horse. We can start off with the horse being successful right off the bat

and when a horse is successful we pet him and begin building trust and building enthusiasm

for the training.

Next in the lesson plan is to put as many steps as possible between your starting point

and the goal. Again, like pages in the book, the more we break everything down the faster

the horse reaches the next step – the next level in the lesson plan, the next page in

the book. Learning the formula for developing a good lesson plan is critical in training.

It keeps us out of trouble, keeps us out of fights with our horses, prevents

misunderstandings.

I see a lot of people with a goal but they have no clue as to where the horse is - what

level the horse is trained to. They are trying to get him to do things halfway up the

lesson plan and they have not even covered the first part of the lesson. They do not know

where they are and do not know where they are going. The chances of being successful under

those circumstances are just astronomical.

I see people with a real vague idea of what they’re trying to accomplish, for

example, they want to clip the horses’ ears. They want to be able to clip their

horse’s ears but they can’t even touch the horse’s ears without a fight.

There are 100 –200 steps between being able to touch the horse’s ears and

putting the clippers on his ears. Each step is a page in a book. You shouldn’t expect

him to have all the knowledge of everything in the book until you give him the last page,

the clippers are the very last page.

Learning how to develop a lesson plan is a skill, it is an acquired knowledge we put into

practice which eventually becomes a skill.

Equerry: Thank you, John Lyons.

|